Book review: Structure & Interpretation of Computer Programming

What’s the difference between an expression and a statement?

What makes code imperative or declarative?

What does it really mean to program at different levels of abstraction?

I’ll confess, I thought I knew the answer to those questions. Early programmers learn assignment, for-loops, and if-statements, all the way from ‘hello world’ to to-do list apps. We move on from the fundamentals pretty quickly.

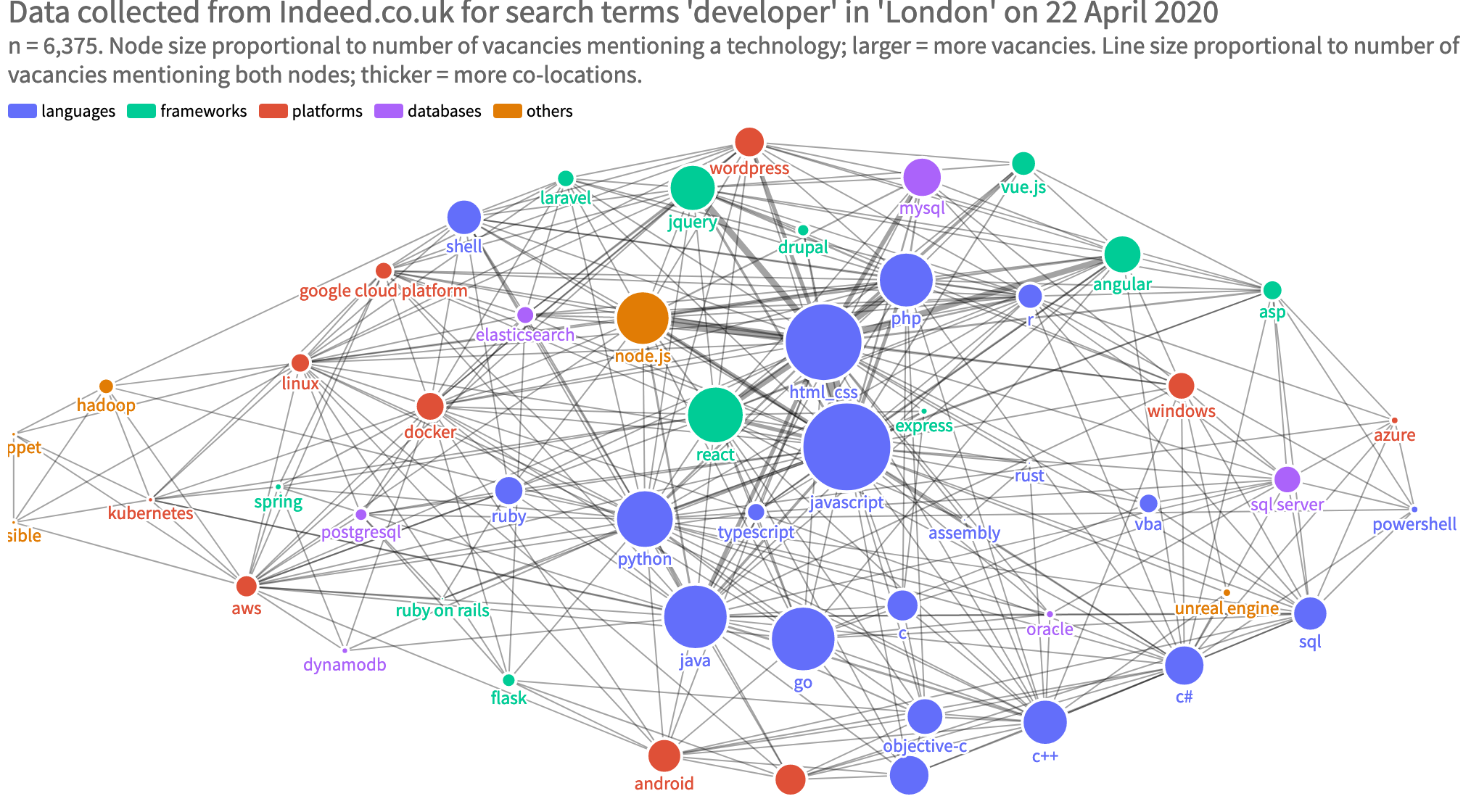

Soon we discover a shiny world of things to learn: distributed systems, GraphQL, machine learning, whatever else is flavour of the month. Who would want to go back and re-tread old ground when there’s so much out there and the blogosphere hounding you to go learn it?

Choosing to study Abelson & Sussman’s Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs (SICP), then, is a risk. But it’s a risk worth taking.

What is SICP?

“The Wizard Book”

SICP is a computer science textbook that introduces the fundamental practice of programming. I say “introduces”, but it is far from introductory.

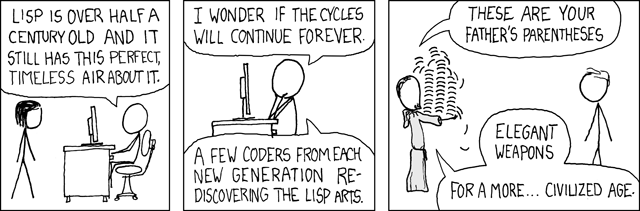

Other learning materials use high-level popular languages like Python, JavaScript or Java. SICP uses LISP.

There are very few keywords or other special exceptions to the LISP syntax, which makes elucidating concepts like recursion, abstract data structures, higher-order functions and state so much clearer than they would otherwise be in a language with lots of syntactic sugar.

XKCD 297 knows

Most fundamental texts and courses also start off with imperative programming using statements (do this, then that, assign this value to that variable, mutate the world). SICP re-programs your brain to think functionally. You get a thorough grounding in concepts like functions-as-data and referential transparency.

A pure function returns a value for a given input, so if functions have values, what makes them different to any other data structure? Sounds simple, but the abstractions you can build on that concept are mind-blowing. Every section of SICP expands on a similarly mind-warping concept.

Once you’ve been re-programmed to think functionally, SICP then introduces you to local state and object-oriented programming. This won’t be new to many, but coming hot on the heels of several weeks of thinking functionally it contains many valuable lessons.

You come away from these chapters with new respect for the difficulties of programming with local, mutable state.

In this sense, SICP isn’t a book on “how to program” so much as an interactive history of how the practice of programming has evolved over the years and how different approaches suit different problems.

(The TL;DR of SICP is, for me, eradicate mutable state from your systems as much as you can at any cost.)

Another mostly good thing in my view is that SICP really does expect a great deal of prior knowledge from you. Page 28/600 uses Newton’s method to introduce recursion. Come on SICP, wouldn’t Fibonacci have sufficed?

It doesn’t get any easier from there: you must be willing to go away and find out answers to things the book expects you to already know, particularly in a mathematical sense.

But that’s what makes SICP such a great resource: it doesn’t matter how many years of experience a reader has, the sheer depth of the text gives new insights.

For me, this sets it out from any other book on the fundamentals of our craft.

If you’re still not convinced, Berkeley lecturer Brian Harvey has an excellent essay on why SICP matters.

What about the downsides?

It’s not all grand, though.

I mentioned the expectations of prior, mostly mathematical, knowledge. One of the best things about SICP is its intellectual rigour and just how challenging it is, but I found some of the chapters relied too heavily on the reader’s mathematics abilities.

Maybe this is an indicator of a gap in my knowledge; maybe the book could have helped me understand its lessons without requiring mathematical fluency. But the sad fact remains that some of the thornier lessons require a level of understanding many potential readers don’t yet have. And this is sad, because what’s hiding beneath is so valuable.

The real value of SICP is in its rigour, and reduced accessibility may be the inevitable trade-off.

Another limitation of SICP is the difficulty in getting some of its examples working.

I used Brain Harvey’s CS61A lectures to guide me through the book, as recommended by teachyourselfcs.com. Harvey’s course uses helper libraries to simplify the exposition of, among other things, object-oriented programming and concurrency.

Sadly, in the ten years that have elapsed since the course material was published and the 25 years gone since the second edition of SICP, software rot has made some of the book’s examples executable only with great difficulty.

This only applies to some example, but if you’re worried about software rot and being able to execute every code example, you might choose instead to study Composing Programs, which is “in the tradition” of SICP.

But does it make you a better programmer?

We’re a pragmatic bunch, us software engineers. We want learning to have a positive return on our time invested, and we want it quickly. What practical value does a 25-year old book about software fundamentals have in 2021?

Essentially, fundamental understanding and a strong mental model of how systems work is pre-requisite for further learning.

Very abstract, I know, but what are the applications?

I’ve found in code reviews that state mutations stick out like a sore thumb after reading SICP. Occasionally code like this makes its way into pull requests:

// bad juju

let users = [];

users.push({ id: 1, name: 'alyssa p. hacker' });

users.push({ id: 2, name: 'ben bitdiddle' });

// some time elapses

users.push({ id: 3, name: 'steve stevington' });

users.forEach((user) => (user.processed = true));

Many people see nothing wrong with this. I used to do this all the time. If the language allows it, why not do it?

SICP gives you the burden of knowledge.

Other parts of the system will eventually operate on the mutable users variable, maybe poping, maybe altering one of the elements. Far better to keep things immutable and avoid difficult-to-trace bugs.

// better juju

const users = [

{ id: 1, name: 'alyssa p. hacker' },

{ id: 2, name: 'ben bitdiddle' },

];

const newUsers = [...users, { id: 3, name: 'steve stevington' }];

const processedNewUsers = newUsers.map((user) => (user.processed = true));

This is a very simple example. Others include using higher-order abstract functions to improve both readability and modularity.

For example, at work this week I wrote a recursive function to diff two objects:

const diffObjects = (base, comparator) => {

/* return an object containing the keys that appear in both base and comparator, but are different in comparator.

For example:

const base = { a: "b", c: "d" }

const comparator = { a: "b", c: "e" }

diffObjects(base, comparator) // { c: "e" }

*/

};

Very low-level, but how do we use it?

In the application we’re developing, we need to ensure only updated data is PATCHed to the API so that our system behaves in a conventional way.

To achieve that we diff what the user submits from a web form against the existing state of what is being updated.

This is a much higher level of abstraction than diffing two objects, so we raise it like this;

const updatedValues = (before, after) => diffObjects(before, after);

This renaming makes the temporal before/after element in this use clear, and distinct from the low-level “compare two objects” meaning of the diffObjects function.

We could also raise the same function to an even higher level of abstraction, making it a completely domain-specific.

const diffDomainEntity = (entity1, entity2) => diffObjects(user1, user2);

This way of thinking about programming - building layers of abstraction to the point that code reads like a high-level domain language - is central to the lessons of SICP and something I think about every day at work.

So: go ahead and learn GraphQL/machine learning/AI/big data/whatever flavour of the month is currently, but before you do, pick up a copy of Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs. You won’t regret it.