JobscraPy: a Python web scraper for job vacancies

I started this project because, like many career changers, I wanted to know what ‘stuff’ I should learn to best improve my chances of getting a software engineering job when I leave my current industry.

Alas, a lot of the guidance online is mostly individuals’ conjecture based on what they’ve seen working in Silicon Valley or, worse, an attempt to sell you a learning resource.

Where UK data does exist, it’s frequently abstract to the point of uselessness: did you know that JavaScript is a popular programming language among UK employers?

Enter jobscrapy.

The brief

Create an app to scrape job vacancy data from the listings website Indeed.co.uk.

App should take as arguments the location being searched and a string of search keywords. For example, this search for ‘junior developer’ in ‘Bristol’ using Indeed.co.uk’s web interface:

The resulting job vacancies must be stored in a format appropriate for future use in a variety of applications.

The following fields must be stored:

- Job title

- Company

- Location

- Salary (if advertised)

- Description

- URL

Why is this important?

You might have been told this:

“The specific programming language isn’t important: it’s the principles, core skills and ways of thinking that count.”

That is true, but at some point you’re going to have to learn those core skills by writing some code.

And, rightly or wrongly, we’re still in a world where job vacancies advertise for a ‘PHP developer’ with x years of experience rather than a generic software engineer with a good grasp of the principles.

With so many learning opportunities out there, I need to know the best way to learn both the principles and the skills with specific technologies that employers say they want.

This is important because of opportunity cost: time spent learning Python/SOLID principles is time not spent learning PHP/TDD. Over to you Dilbert:

Computer science is also about optimisation: if you’re doing a side project for the love of learning, why not do it in a language that’s also associated with the greatest opportunity for paid work in your area?

What I did

I started working with the third-party Python library Beautiful Soup. This allowed me to scrape and query the DOM for a given search term’s results page.

From there, I could pull out the relevant data fields relatively easily.

Next was where the hard work started. How to reliably get that data from Indeed.co.uk in a way respectful of not overloading its servers? How to get meaningful location and salary data from the result?

Here’s a rough breakdown of what I encountered on this journey.

Geocoding locations

I make no secret of my love of maps. Terrain analysis was one of my favourite parts of my job as a Royal Marine.

The ‘where’ of these job vacancies was also very important to me. There’s no point in gathering vacancy data for jobs that the user can’t get to.

The difficulty is, location data on job vacancies is particularly generic. No employer puts their full address, with most just listing the city. Location strings such as ‘East London’ or ‘Bristol BS2’ were common in the raw data.

To solve this, I created an account with Google Maps Platform. The free tier here is quite powerful and Google Maps’ location data is the best I could find.

Using the GeoPy library, I then created a set of functions to:

-

Attempt to geocode using the

companyname and thelocationfield of the job vacancy. So if the company name is “McVitie’s” and the location is “Carlisle”, attempt to geocode “McVitie’s Carlisle”, which should return a GeoPy Location object with the latitude and longitude of the factory where Hob Nobs are made (at 54 Church St, Carlisle, CA2 5TG). -

If that returns

False(“Biscuit error: Hob Nobs not found”), attempt to geocode thelocationfield and thewheresearch term. So, if you search for a keyword inBristol, this step will attempt to geocode a single job listing’slocationfield nearBristol. This is less accurate than step 1, hence that being attempted first. -

If all else fails, just geocode the

wheresearch term. This will return a latitude and longitude that’s in the same city at least, though it may suggest that a job is located in the city centre when it’s really in the suburbs. (It’s debatable that I should have just had it returnNonewhere no suitably accurate geolocation is made, as inaccurate data is in some cases worse than no data.)

The code snippet for this functionality is here:

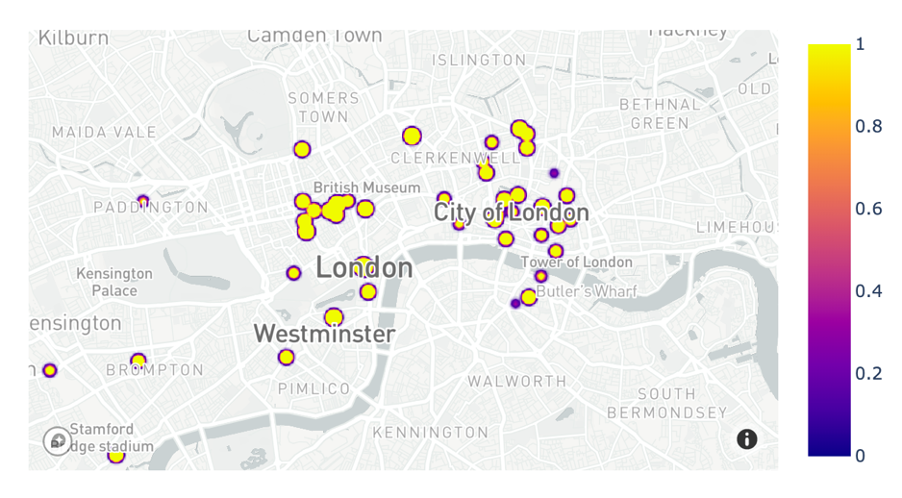

This allowed me to show each vacancy on a map, like below:

(More on findings from the data later and in a separate blog post)

Being respectful of third party services

Wrapping the geocoding code block is the decorator function retry() from the library retrying:

@retry(wait_exponential_multiplier=1000, wait_exponential_max=60000)

This helps me stay within Google Maps’ usage limit of 50 Queries Per Second (QPS). By leaving it at 1,000 milliseconds (1 second), my function only backs off once it’s hit the API’s limit, not before. A more elegant solution might deliberately rate limit the function to sit beneath Google Maps’ 50 QPS. I decided to go with the less elegant but more reliable use of the @retry decorator.

(The wait_exponential_multiplier is an implementation of exponential back-off, a key concept in computer science theory and an essential part of networking. It’s very useful for accommodating unreliable services beyond a dev team’s control, such as a third-party API or website in the process of being scraped… There is a really accessible discussion of exponential back-off in Brian Christian’s book Algorithms to Live By.)

When things go wrong (or: writing exceptional code)

My work up until now has been predominately in the happy path. Relatively straight-line stuff that doesn’t rely on external services and where there isn’t much room for user misbehaviour.

This project introduced several unpredictable moving parts where things might go wrong:

- Requesting each web page from Indeed.co.uk.

- The geocoding functionality described above.

- Saving to file.

This caused me to cut my teeth on error handling.

Chapter 7 of Uncle Bob’s Clean Code is really good for this, if it does require a bit of on-the-fly Java comprehension. The basic principles are:

- It’s generally better to try to execute a code block and handle what happens if things go wrong than write lots of conditional, input-checking code to avoid things going wrong in the first place. (in code, as in life…)

- Separate the concern of error handling into one place away from the main logic.

- Use informative messages when things do go wrong.

(Important distinction here between an ‘error’, which cannot be handled and are fatal to a program at runtime (e.g. syntax error), and an ‘exception’, which can and should be handled to improve the robustness of the program.)

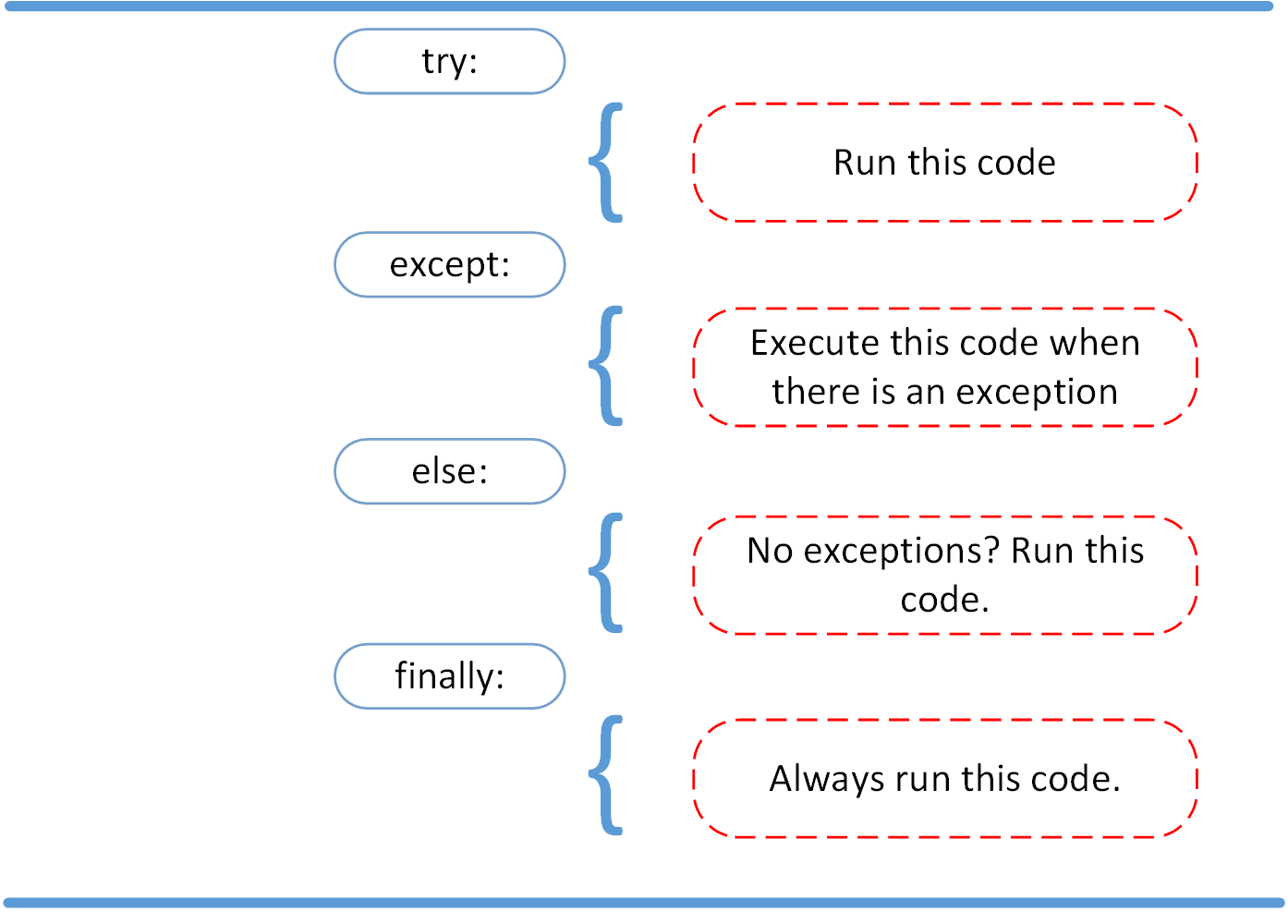

Python handles exceptions using try:, except:, else: and finally: statements:

Here’s how I did it:

def main(args):

try:

# <Main function of the code here>

except OSError as err:

print ("Looks like something went wrong with the file operation...")

raise SystemExit(err)

except requests.RequestException as err:

print ("Looks like something went wrong with the requests operation...")

raise SystemExit(err)

except geopy.exc.GeopyError as err:

print ("Looks like something went wrong with the geocoding operation...")

raise SystemExit(err)

except Exception as err:

print("Unexpected error.")

raise SystemExit(err)

The methods that are called in the try: code block do not contain any error handling code, they just raise the exceptions normally when things fail, which are then caught in the main() function here. This separates things, keeping the concern of “what to do if there’s an error” limited to 11 lines of code in one place.

Arguably, my error messages are not fantastically useful. They point to concepts/functionality that in my mind made sense, but another developer may have difficulty with on picking up my project. Looks like something went wrong the with geocoding operation... should probably refer to the JobAd.geocodeLocation() method specifically, for example.

Although, as a counterpoint, naming functions/methods in error messages (and comments) can create a closely-coupled system that’s difficult to change. Changing the JobAd.geocodeLocation() method (or even the entire class) would cause a corresponding error message to be incorrect.

(I genuinely don’t know the answer to this and, dear reader, would greatly appreciate your thoughts if you wanted to contact me on Twitter or LinkedIn. These are things I’m looking forward to understanding from other developers how things are done / should be done in industry.)

Other design decisions

Sometimes a job vacancy in Indeed.co.uk wouldn’t have a field, or the field would be expressed in different ways that I’d have to handle. This isn’t error handling, but accounting for different inputs that I know are present in the data.

For example, my getRawSalary() method can take None or a string as an input:

def getRawSalary(self, result_element):

salary_element = result_element.find(attrs={"class":"salaryText"})

if salary_element is None:

return None

else:

return salary_element.string

Have I done the right thing here?

I read in Thomas and Hunt’s The Pragmatic Programmer about Design By Contract, and particularly liked the summary phrase:

Be strict in what you will accept before you begin, and promise as little as possible in return. Remember, if your contract indicates that you’ll accept anything and promise the world in return, then you’ve got a lot of code to write!

By taking a None value or a string, am I being too lax in what my function will accept?

I think, for this use case, I’m not. None types need to be handled as I know that they exist in the data, yet having the caller perform the is input None? step would remove a lot of the value of abstraction, pulling horsepower up into main() (for each field in the job vacancy) and create a coupling between pre-processing in the caller and the main processing in the method.

Having the relevant method for each job vacancy handle None values instead allows the main() function to be more abstract, obfuscating the complexity of dealing with the different data values that the web scraper might encounter down into the class methods.

You may disagree! Please get in touch, I’d really like to hear what you think.

The result

Despite question marks I still have over some of the design decisions I made, I have a working job vacancy scraper that:

- Reliably pulls all job vacancies from an authoritative listings site.

- Is respectful not to overload the scraped website.

- Queries a geocoding API in an intelligent way, improving the meaning of the data by getting a specific location.

What to do with the data

As a soon-to-be job seeker looking for my first software engineering role, I needed to put the job vacancy data to use.

I scraped three datasets using my tool: one in Bristol on 3 March (prior to the UK’s Covid-19 ‘lockdown’ on 23 March), another in Bristol mid-‘lockdown’ on 21 April, and a third in London:

| name | n | date_obtained | ‘what’ | ‘where |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bristol (pre-‘lockdown’) | 592 | 3 March 2020 | ‘developer’ | ‘bristol’ |

| Bristol (mid-‘lockdown’) | 397 | 21 April 2020 | ‘developer’ | ‘bristol’ |

| London | 6,375 | 22 April 2020 | ‘developer’ | ‘london’ |

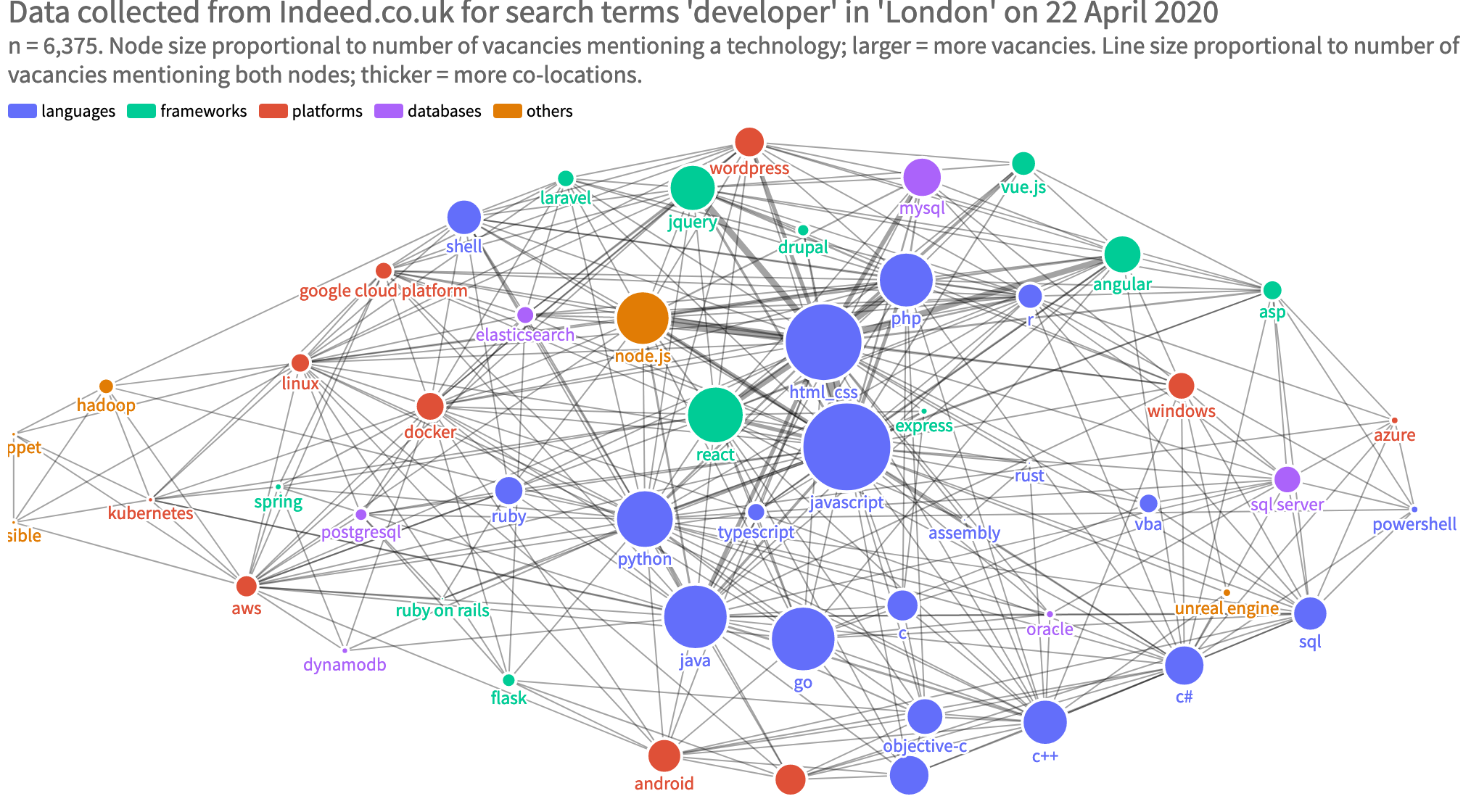

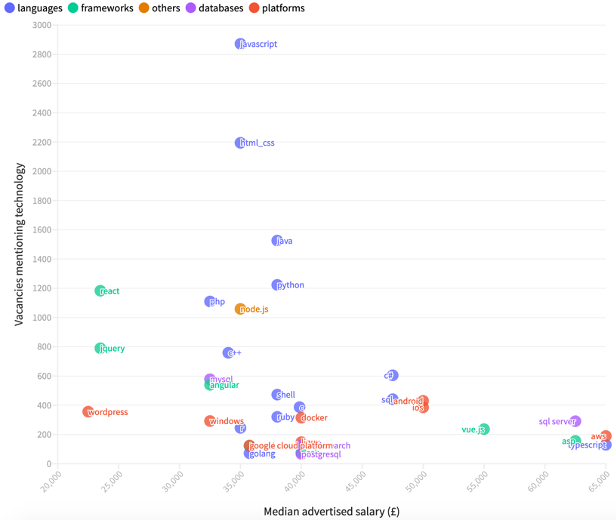

I then used the languages, frameworks, platforms, databases and other technologies identified by Stack Overflow’s developer survey to identify which skills were in demand in the three datasets.

This analysis is the subject for another post, but suffice to say the results, visualised using Plotly, were interesting.

For example, in the London data I found the number of jobs mentioning JavaScript and HTML/CSS were very high, but the median advertised salary was in the middle of the pack. This contrasted with vacancies mentioning Amazon Web Services (AWS), SQL Server, Typescript and ASP, which were comparatively few in number but associated with a higher median advertised salary:

Relationship between median advertised salary and number of vacancies in the London data

Relationship between median advertised salary and number of vacancies in the London data

(Noting that only 31% of vacancies advertised a salary, there are other limitations to the findings the data can reasonably provide.)

A network graph of the skills across all the job vacancies was also really cool to play with:

What I learned

There’s so much I dipped my toes into here, but the two main takeaways were undoubtedly:

- More to learn about object-oriented programming and clean code. This was my first foray into object-oriented programming. Python isn’t particularly opinionated on OOP (like Java), so it’s been a bit of a challenge to know if I’m doing it right. Attempting to write OOP Python whilst implementing some of Uncle Bob’s Clean Code was a steep learning curve, though even if I didn’t get it 100% right this time I feel better equipped to continue this voyage of discovery as a result.

- Error handling. Making my app work with unreliable third party services was a real challenge and took me off the ‘happy path’ and got me thinking about ways to make my code more defensive. With a 1 - 2 hour + execution time for really large datasets, it would have been unacceptable for a user to come back to my app and realised it had crashed, so it’s right that I got stuck into this.

Future learning opportunities

- Learn OOP properly. I’ve dipped my toes in OOP having tried to grok Uncle Bob’s SOLID principles using the Java examples he gives. This has been sub-optimal, as you can probably tell by my codebase. Instead, I need to pick a book or course on OOP in a language that’s familiar to me. Dusty Phillips’ Python 3 Object oriented Programming looks a worthy candidate.

Summary

There is a saying that a little knowledge is dangerous.

I think I’m in that territory here: by working through Clean Code and The Pragmatic Programmer I’ve exposed myself to many of the important concepts in good software design, but I’ve pulled them together in ways that perhaps don’t make the most sense.

I’ve learned a lot from this project, not least that there’s much more to be learned!

Onwards and upwards.